3. Personal Memories: The Start of DENSO International America

DIAM: Part of a Global Localization Strategy

DENSO had been in the Detroit area for nearly 20 years when word raced across Southeast Michigan that the company would be creating a larger presence there. It was a bold move designed to attract market attention and signal to key customers that DENSO was once again ahead of the automotive-needs curve.

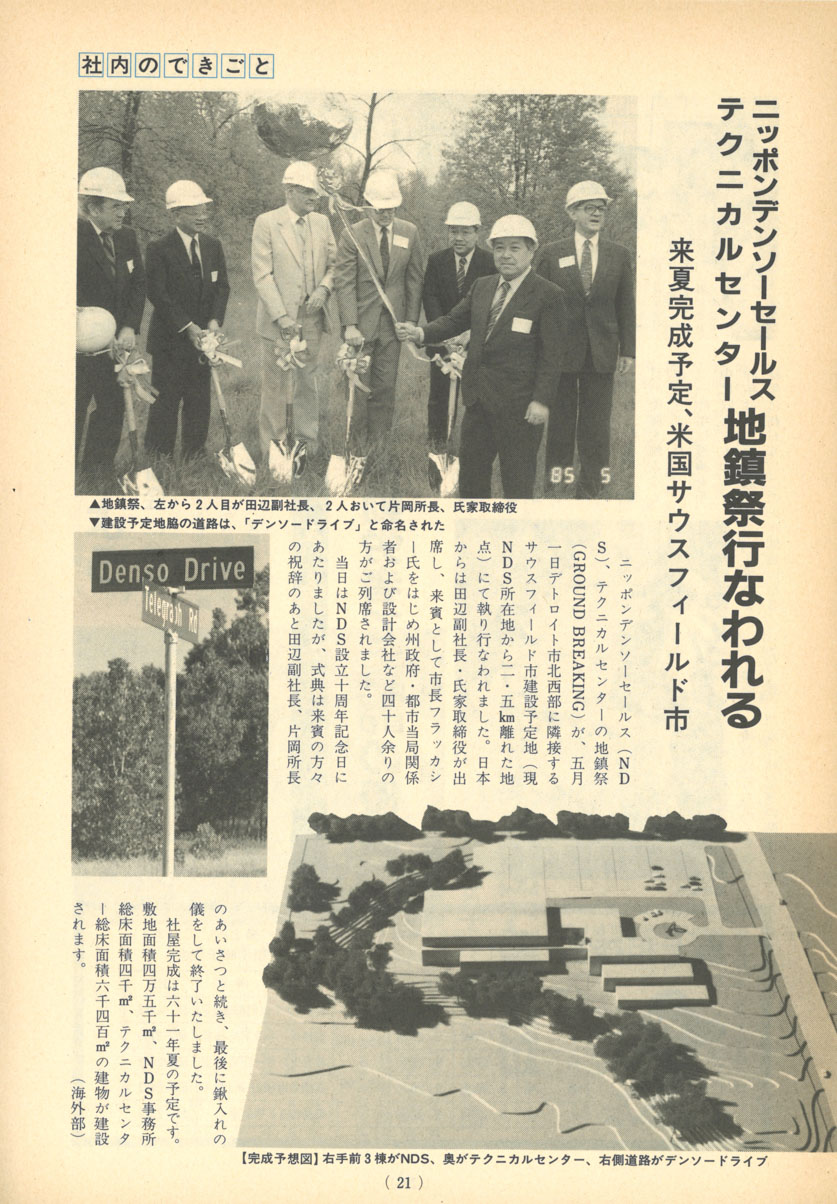

Located in Southfield, Michigan, just outside of Detroit, the newly named Nippondenso America Incorporated was to be the first U.S.-based technical center by a Japanese supplier, and the company’s first regional headquarters outside of Japan. It was 1985.

Nippondenso America Inc., which became DENSO International America (DIAM) in 1996, was destined to serve as a foundational business pillar by providing more extensive and agile technical services locally, while creating a cohesive business system for DENSO’s growing North American operations.

“Above all, our biggest objective was to have regional headquarters in North America, which would integrate management and coordination of all our North American bases for a single market,” explained Chosei Ujiie, former Executive Vice President at DENSO, and author of Milestones of International Operations, 40 Years with DENSO. “The technical center was built … to cultivate development capability in the United States, as well as transfer technology from Japan.”

R&D: A Competitive Advantage

The primary architect of DENSO’s global strategy at the time, Ujiie envisioned associates in Detroit working collaboratively to promote sales and engineering to Chrysler, Ford and General Motors. Further, with the new technical center, he understood that the scope of DENSO’s work here would expand to include research and technology development.

In fact, the opening of DIAM quickly came to serve as a highly respected model of a cutting-edge company exhibiting efficiency in marketing, engineering, public relations and external and legal affairs.*

What’s more, DENSO’s timing couldn’t have been more opportune, as American automakers were now actively seeking new technologies and suppliers to both reduce costs and increase quality.

Just 19 years after Andy Kataoka had begun his quest to supply Detroit’s automakers, he was now leading DENSO’s first offshore headquarters. Under his watch, DIAM would quickly become a unifying element and coordinating home-base in the region. And as the 21st century approached, regional strength would become essential to responding to unprecedented global challenges.

*Proud Past, Strong Future, A History of DENSO’s First 50 Years, page 146.

East Meets West in the Motor City – Associate Accounts of Early DIAM

As DENSO jump-started its first headquarters and technical center outside of Japan in 1985, it sent a cadre of associates from Japan to Detroit, imbued with the DENSO Spirit and equipped with engineering and production expertise. To that mix, they added a team of eager American engineers, sales associates, and professional and support staff … many fresh out of college and starting their careers.

What follows are their collective memories of early life at DIAM.

Read on to experience, in their own words, personal accounts of first-time brushes with international team members; ingenuity in communicating without a shared language; the 13-hour time difference that had one team going to bed as another got to work; the adrenaline rush of a start-up atmosphere; and shared opportunities to be part of DENSO’s, expanding universe.

Karen Croly joined DENSO in 1979, and served in a variety of administrative functions, most recently with the DIAM purchasing team. This memory was penned in June 2017.

Nippondenso in Southfield, Michigan, had 20 associates when I joined, and shared a building with a bank and a parking lot with a bowling alley. The machines we used to communicate in the early 1980s no longer exist. The Western Union Teletype machine provided notes from banks on small ribbons of paper.

Our suppliers in Japan communicated via the DEX machine, which used a phone line and sheets of silver-oxide coated paper. It took up to six minutes to produce a single sheet, and the process filled the office with an unpleasant burning odor.

It was a great day when the fax machine arrived. The Ricoh fax was faster, cleaner and clearer than anything we had used before. Faxing was new to us, and our Japanese associates were very curious about how it worked. The fax machine was delivered on a Thursday, and we all received training.

I arrived at work the next morning and began gathering communications from the night before to distribute, which I always did. But this morning, I entered our communications room to find our newly acquired fax machine neatly laid out – in approximately 100 pieces – on the floor.

Our curious engineers had disassembled the fax machine the night before and couldn’t put it back together before we arrived the next morning. I recall the uncomfortable conversation with the vendor requesting assistance!

The vendor was very accommodating, which leads me to believe DENSO wasn’t the only company attempting to “see how this new machine worked.

Doug Patton joined DENSO in 1986 as the Manager of Heavy-duty Sales. Before he retired in 2019, he was Chief Technology Officer and Executive VP of Engineering in North America.

DENSO had a great reputation for delivering on its promises. I came onboard as soon as the new location was completed and immediately began acclimating to a Japanese employer half a world away. It was a completely different culture that revered relationships, wisdom and experience. My strategy was to explore the pros and cons of everything and to master the system because there was no “beating the system,” which is a very American thing to try.

With our track record of successful production launches and high-quality products, the American automakers began to accept the quirks of working with DENSO. Sometimes our Japanese counterparts asked so many questions it drove us a little crazy. As a result, part of our job included anticipating the next question, asking it together, with the auto manufacturers, and pushing back on unnecessary questions.

The bottom line? When the product went to production there were no problems. One manager said to me, “DENSO is a real pain to work with, but I don’t have to see you after launch.” This led to more product opportunities.

At the beginning, roles were fluid, and we each did what had to be done. Japanese leadership was engaging and supportive but challenging. Success depended on the ability to push your opinion and back it up with data. Not just once, but several times.

There’s a Japanese proverb that says, “if it’s not worth challenging three times, it is not important, but don’t waste your time with a fourth try.” This frustrated some but if you believed in yourself … they would listen. This was a way to build respect.

At first, teams were a 60/40 mix of Japanese and American associates. Every group had a technical expert and manager, who were expatriates with connections to the product group in Japan.

I created relationships with everyone at DENSO in those early days, which was a great feeling. DENSO was different because of the quality of the whole experience, for customers and associates.

Gayle Lark joined DENSO in 1987 as an Engineering Assistant.

Each assistant worked for a handful of engineers. After typewriters, we got Xerox GlobalView computers for each section. These were the first Windows-type systems, and assistants had their own machines. We created all the documents for our section, which were provided handwritten by the engineers.

When things got so big and busy that the assistants couldn’t keep up, PCs were supplied. Engineering assistants’ responsibilities evolved from simple typing and creating documents, to assisting groups with manpower management, budgets, travel, and many other duties. We were able to keep up with the growth in our departments thanks to technology.

I have fond memories of the parties in the early days. We held them in the “auditorium,” in DIAM’s Technical Center. A wooden dance floor would be brought in, a DJ hired, and Yoshi (i.e., café chef and sushi master) would cater it with all kinds of wonderful food. It was very elegant, and for the first few years, each associate received a wrapped gift. The parties, picnics, etc., were a great way for us to bond.

Other notable memories:

When a Japanese associate was saying farewell, the group used to gather and toss the person into the air!

Assistants dressed more formally, wearing dresses and skirts. Men had ties, and many wore white company jackets.

It was great having our own cafeteria and chef! Back then, the American menu was hamburger, hot dog, or pizza, and all with fries.

When the micro-car (a working vehicle the size of a grain of rice!) came to the U.S., it was featured on Tim Allen’s TV show, “Home Improvement.” Shink Omi and Marlene Goldsmith “babysat” the micro-car, and both went to Los Angeles for the filming of the “Home Improvement” episode. Shink brought me back a Home Improvement T-shirt signed by Tim Allen! He was a wonderful man, and I remember him fondly.

I always appreciated my time with DENSO, the people, and the relationships I formed. DENSO is a good, steadfast company —I haven’t seen a full-time associate layoff in all these years. There has always been a sense of pride, without being too showy, and I have found the mix of cultures stimulating and educational. It’s been a great place to have a career for the past 30+ years!

Dwayne Taylor joined DENSO in 1986 as an Engineer. Today, he is a Research and Development Engineer.

I joined DENSO from college and understood immediately that they wanted associates for life. The culture was to grow, develop, be challenged and enjoy doing our work, which we did.

I was part of a small thermal group just six of us. Today there are several hundred. We were focused on business expansion, creating product presentations for customers, responding to RFQs (i.e., Requests for Quotes), and supporting the Ford/Mazda joint venture.

At first, engineers at DIAM focused on applications. We sent design and product-related questions to Japan using faxes and phones. No computers.

With the new building came the capability to test, and testing capabilities only grew from the day DIAM opened. DENSO created a lab with a wind tunnel and evaporator chamber and could test air-conditioning systems and compressor dynamometers. We could do solar testing, four-wheel drive, and it was large enough for excellent airflow around the vehicle.

The wind tunnel supported local customers looking for design, development and validation. Our customers wanted to see the test and participate in the testing parameters. By using the wind tunnel, we significantly boosted our product knowledge and expertise. The tunnel allowed DIAM engineers to begin thinking in terms of systems and dramatically accelerated our product development and innovation.

We learned that DENSO engineering culture means paying attention to detail, working through issues completely, having high expectations, understanding that our product development, and the final end-user, is impacted by the work we do.

It was and still is a positive experience working with Japanese associates.

Debbie Agar joined DENSO in 1987 as administrative support staff.

There were approximately 70 people at our Southfield, Michigan, location, and I worked with 11 of them: eight from the powertrain team and three from electronics. Toshi Ohtake led our team.

We didn’t have voicemail then, so we answered the associates’ phones when they were away from their desks. We got to know our suppliers that way. We didn’t have computers, either. A big part of our morning included gathering faxes received overnight, copying them for the people “cc’d” and distributing them to mailboxes.

We did have typewriters with memory. And we created presentation materials using a literal cut-and-paste method. We taped the edges of pasted portions to avoid outlines when we made final copies. Sometimes we worked on Saturdays to complete material for early-week presentations.

Around 1991, the technical center received its first Globalview computer, which made creating presentations easier with a more professional-looking final result. The problem was that we had only one for the admins, which meant we had to reserve time on a sign-out sheet.

We worked with a travel agency to book tickets. No computers meant taking what the travel agent gave us and getting paper tickets well before travel dates, which could be tricky because of schedules and no cell phones to call or text.

We have a great group of engineering admins who are now great friends. It was a great place to work while raising my family.

Rob Martin joined DENSO, in 1988 as an Engineer. Today he’s an Engineering Project Senior Manager.

When I joined the alternator group, there were two Japanese associates and me. This was the typical team make-up at the time. There were growing pains for both cultures working together.

We overcame differences, because we all supported the goal to grow and add capabilities. We focused on that goal and helped each other in any way we could. They needed us to interface with the customers, and we needed them to interface with Japan.

Once we built the plant in Maryville, Tennessee, in 1988, the future was bright for alternators and starters. Significantly because we could get our products in the states, and we could innovate in the states. Now, that plant is phasing out starters and alternators, converting to electronic components.

It’s 1994 and our customer wants DENSO to summarize the proposal for alternator service parts we’ve been discussing. “Tell us what you want to do, show us the example pictures and details,” they said.

In 1994 that meant:

Using a 35mm camera with film to take pictures

Getting two sets of photographs developed, which took a few days

Using scissors to cut out desired areas from selected photos

Handwriting all needed text and tables

Using Liquid Paper or white-out tape to fix mistakes

Photocopying each page to share with the customer.

We were pretty good with the scissors, tape and WRITING BY HAND, but I much prefer the technology.

Being a DENSO associate has positively shaped who I am. I have strong attention to detail in every aspect of my life. I listen first, think and then speak. I am a better communicator.

Tim Roland came to DENSO in 1991, fresh from Michigan Tech. Today he is a Director of Engineering.

“We were the biggest auto supplier no one had ever heard of. DIAM started out with one large building and approximately 100 people. Today, there are close to 2,000 that are spread across a five-building campus with testing and technology.

As a new engineer I had responsibility for an entire vehicle system: design, drawings, testing – DENSO leadership supported us, mentored us, but encouraged us to take ownership and provide our own thoughts and plans. This was unique: my friends at the carmakers were only designing components.

We learned that every customer needs to be treated individually. We matched our role to what the customer needed. Chrysler wanted high collaboration, and we helped them with documentation and specs. GM provided books of specs but wanted an R&D partner.

GM thermal represented a huge expansion of business and responsibility. It was system level, and we were growing from behind the dash to under the hood. Through collaboration with GM, we built trust with the customer and gave them confidence in DENSO expertise.

The wind tunnel emphasized DENSO’s commitment to Detroit automakers. We could test thermally, aerodynamically, engine loads, how rapidly windshields cleared, the entire vehicle.

Being young and travelling in the early 90s was a great experience. Before computer models and the wind tunnel, we took road trips to test our parts. We went to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, the Rocky Mountains, beaches in Texas, Alligator Alley in Florida, the steep hillsides outside of Las Vegas, even Graz, Austria. We were validating max loads, engine heating and cooling, and what happened when water washed over the car.

Together, with engineers from the carmakers, we were problem solving, discussing the give-and-take of systems’ interactions and, most important, we were building relationships.

When I joined, DIAM was a four-year assignment for our Japanese associates. They worked with us all day and then put on comfortable shoes and worked into the night with the teams in Japan. But as our local expertise grew, as we added capabilities, we began assuming more responsibility and leadership roles.

I look back very fondly on my career at DENSO. It was a great way to start. We were a team of young people in 1991 working hard but within a social environment filled with strong camaraderie.

Jon Hill joined DENSO to commission and operate DENSO’s state-of-the-art wind tunnel.

We worked many long days fixing issues with the chamber and learning how to use it. Our first real test was on a motorhome in February 1993. Since then, we have tested all kinds of things from Fleetwood motorhomes to John Deere tractors. We tested the first air-conditioning system in a Dodge Viper.

Later, we had an open house for our families and created a model airplane attached with fishing line and flew it with the tunnel air. I remember Mr. Watanabe, Tech Center Executive VP, coming to the wind tunnel and playing with the plane’s control lines. He had the biggest smile. I have spoken to the kids present at that open house, and they still remember that airplane display.

When I think back, we have made huge improvements in our testing abilities. DIAM has come a long way!

Dennis Dawson joined DENSO in 1993, as Director of a non-existing legal department. He retired in 2011, as Senior VP, General Counsel and Corporate Secretary at DIAM.

In an American company, when creating a report, you study something, prepare a lengthy document with a simple overview and then share it with an executive. But in a Japanese company, at DENSO anyway, you created what I called a Japanese chart.

Japanese charts had a horizontal row with the factors evaluated and a vertical column with identified choices. And innate in that framework, you synthesized the issue and options to key points and then literally, the resolution was evaluated with two or three different characters, usually an “X,” triangle or circle, to show the recommended choice.

Then you went to an executive with that prepared chart – and all the background material developed, in case they asked for it – and started with your recommendation. The chart initiated robust discussions about various alternatives and why one was recommended while another wasn't.

DENSO Japanese associates are excellent long-term planners and planning always followed our chart discussions. Engaging at that level was new to me and provided an interesting and challenging opportunity.

My desk was in a bullpen-style area next to an executive vice president from Japan, who had interviewed and hired me. He had a younger Japanese manager who was part of the interview process. I soon realized that these very modest Japanese executives, who sat out in the bullpen at ordinary desks, were key leaders at DIAM.

Every day I watched associates discuss things with him. Obviously, he and his coordinator were key people at DIAM and, to my surprise, they began to engage me in activities that proved to be of particular importance at that time.

That Japanese executive went on to become the best boss I ever had and, when he returned to Japan, became a director of corporate services for DENSO worldwide. Eventually, the coordinator became my boss, too.

I was incredibly lucky to come upon these two people early in my career. Under their guidance, I learned how to work within DENSO, understand the Japanese culture, and be successful. I have great admiration for both of them.

Some of my best memories are from the Southfield campus expansion. Not only was the legal work interesting, but it felt like we were part of something bigger as we transitioned from our smaller staff to integrating with the larger DENSO footprint in North America.

I wouldn't have traded the opportunity to be at DENSO for anything. And I am forever grateful to the former law firm colleague who encouraged me to apply for the new corporate attorney position here. He knew this was the chance of a lifetime and told me I wouldn’t regret the decision – he was absolutely right!

Tianjin Liu joined DENSO in 1993 as a Senior Design Engineer. Today he is Senior VP of Engineering.

Throughout the last 30 years, the changes at DIAM have been drastic. There were six people in our group in ’93: three from the U.S., and three from Japan. We hardly used laptops and chiefly communicated by fax. We were still using CAD 2D design with all drawings – many – and specs faxed to Japan.

I was brought on because of my experience in 3D design and Catia, which is considered advanced CAD design. I joined because DENSO offered advanced design, training and R&D. In 1993, NIPPONDENSO was a global company, and positioned as a Tier 1 supplier.

We launched the “World First” EL (electroluminescence) meter, which was designed by DIAM (S rank for early-stage control) for Chrysler LHS in 1998. We also launched the “World First” TFT projection meter, which was designed by DIAM (S rank for early-stage control) for the Chrysler Pacifica in 2003.

Once we had a local design team, we began to earn confidence from customers and trust from Ford, GM, Chrysler, Toyota and Honda.

The Ford Ranger was our first instrument cluster business with Ford and the biggest new piece of business from the Detroit 3, after Chrysler. It was a major milestone award for DIAM. After that, we won Toyota and Honda instrument cluster business for their North American vehicles.

Doors opened at the Detroit 3 after DENSO established local design capabilities, and engineering. We could meet face-to-face and have a deeper understanding of the customer’s needs. Plus, local design engineering meant the expertise existed in North America, and that was important to them.

We began implementing 3D-design engineering with the minivan cluster. We were replacing an inefficient legacy 2D system. Clusters are complicated. They have many parts and hundreds of dimensions on both the prototype and production drawings. 3D allowed DENSO to improve production time, and tooling and die with more robust 3D data.

Again, we were significantly boosting our capabilities.