Personal Reflections: The Start of DENSO International America

DENSO had been in the Detroit area for nearly 20 years when word raced across Southeast Michigan that the company would be creating a larger presence there. It was a bold move designed to attract market attention and signal to key customers that DENSO was once again ahead of the automotive-needs curve.

Located in Southfield, Michigan, just outside of Detroit, the newly named Nippondenso America Incorporated was to be the first U.S.-based technical center by a Japanese supplier, and the company’s first regional headquarters outside of Japan. It was 1985.

Nippondenso America Inc., which became DENSO International America (DIAM) in 1996, was destined to serve as a foundational business pillar by providing more extensive and agile technical services locally, while creating a cohesive business system for DENSO’s growing North American operations.

“Above all, our biggest objective was to have regional headquarters in North America, which would integrate management and coordination of all our North American bases for a single market,” explained Chosei Ujiie, former Executive Vice President at DENSO, and author of Milestones of International Operations, 40 Years with DENSO. “The technical center was built … to cultivate development capability in the United States, as well as transfer technology from Japan.”

R&D: A Competitive Advantage

The primary architect of DENSO’s global strategy at the time, Ujiie envisioned team members in Detroit working collaboratively to promote sales and engineering to Chrysler, Ford and General Motors. Further, with the new technical center, he understood that the scope of DENSO’s work here would expand to include research and technology development.

In fact, the opening of DIAM quickly came to serve as a highly respected model of a cutting-edge company exhibiting efficiency in marketing, engineering, public relations and external and legal affairs.

What’s more, DENSO’s timing couldn’t have been more opportune, as American automakers were now actively seeking new technologies and suppliers to both reduce costs and increase quality.

Just 19 years after Andy Kataoka had begun his quest to supply Detroit’s automakers, he was now leading DENSO’s first offshore headquarters. Under his watch, DIAM would quickly become a unifying element and coordinating home-base in the region. And as the 21st century approached, regional strength would become essential to responding to unprecedented global challenges.

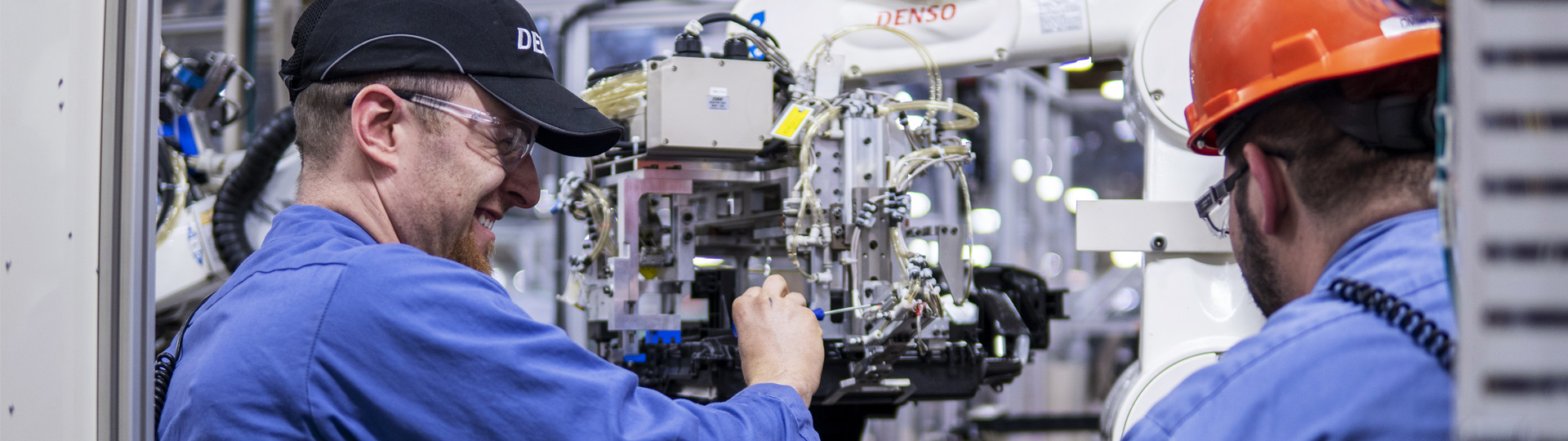

East Meets West in the Motor City – Employee Account of Early DIAM

As DENSO jump-started its first headquarters and technical center outside of Japan in 1985, it sent a cadre of employees from Japan to Detroit, imbued with the DENSO Spirit and equipped with engineering and production expertise. To that mix, they added a team of eager American engineers, sales associates, and professional and support staff … many fresh out of college and starting their careers.

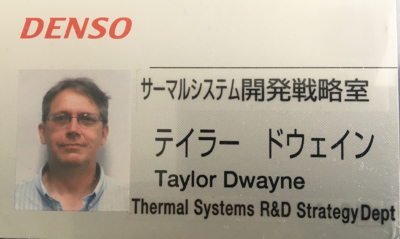

Dwayne Taylor, who joined the Southfield team in 1986 and continues today as a research and development engineer, shared his reflection on what it was like to be part of DENSO’s expanding universe:

“I joined DENSO from college and understood immediately that they wanted associates for life. The culture was to grow, develop, be challenged and enjoy doing our work, which we did.

I was part of a small thermal group … just six of us. Today there are several hundred. We were focused on business expansion, creating product presentations for customers, responding to RFQs (i.e., Requests for Quotes), and supporting the Ford/Mazda joint venture.

At first, engineers at DIAM focused on applications. We sent design and product-related questions to Japan using faxes and phones. No computers.

With the new building came the capability to test, and testing capabilities only grew from the day DIAM opened. DENSO created a lab with a wind tunnel and evaporator chamber and could test air-conditioning systems and compressor dynamometers. We could do solar testing, four-wheel drive, and it was large enough for excellent airflow around the vehicle.

The wind tunnel supported local customers looking for design, development and validation. Our customers wanted to see the test and participate in the testing parameters. By using the wind tunnel, we significantly boosted our product knowledge and expertise. The tunnel allowed DIAM engineers to begin thinking in terms of systems and dramatically accelerated our product development and innovation.

We learned that DENSO engineering culture means paying attention to detail, working through issues completely, having high expectations, understanding that our product development, and the final end-user, is impacted by the work we do.

It was and still is a positive experience working with Japanese associates.”